|

|

|

Greek mythology, a cornerstone of ancient Greek culture, is replete with stories that reveal the intricate web of human existence and the divine forces that shape it. Among these forces, fate holds a prominent and often feared position. The ancient Greeks believed that fate was an inescapable reality, preordained by the gods and inscribed in the fabric of the universe. Let’s delve into the multifaceted role of fate in Greek mythology, exploring its mysticism and the varying perspectives it encompasses.

The Concept of Fate in Greek Mythology

The Moirai: Weavers of Destiny

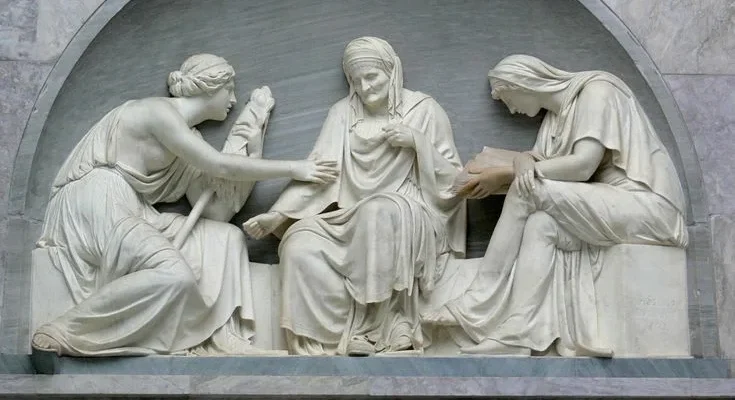

At the heart of Greek mythology’s treatment of fate are the Moirai, also known as the Fates. These three sisters—Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos—are often depicted as old women spinning, measuring, and cutting the thread of life. Each sister has a distinct role: Clotho spins the thread, representing the birth and beginning of life; Lachesis measures it, determining the length and course of a person’s life; and Atropos cuts the thread, signifying death and the end of one’s mortal journey. The Moirai are typically portrayed as being more powerful than even the gods, emphasizing the absolute and unchangeable nature of fate.

Fate and the Gods: A Complex Relationship

Despite their immense power, the gods themselves are not entirely free from the constraints of fate. While gods like Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades wield incredible power, their actions are often seen as being guided by fate. For example, in the epic tale of the Trojan War, even mighty Zeus cannot alter the destined outcome of events, despite his desires. This interplay highlights a complex relationship where the gods can influence but not ultimately change the course of fate.

Mysticism and Symbolism of Fate

Prophecies and Oracles: Voices of Fate

Prophecies and oracles play a crucial role in Greek mythology, serving as the mouthpieces of fate. The Oracle of Delphi, one of the most famous prophetic sites, was believed to communicate the will of Apollo. Individuals and city-states alike sought the oracle’s guidance, believing her cryptic pronouncements to be divinely inspired and destined to come true. These prophecies often contained ambiguous language, leading to various interpretations and sometimes tragic outcomes when misunderstood.

One poignant example is the story of Oedipus, who, despite efforts to avoid his fate, ends up fulfilling the very prophecy he sought to escape. This tale underscores the belief that fate is an unavoidable force, often leading to ironic and tragic twists in the lives of those who try to evade it.

Symbolic Representation in Myths

Fate is not only depicted through characters like the Moirai and prophetic figures but also symbolized in various myths. The tale of Prometheus, who defies Zeus to bring fire to humanity, is one such story. Prometheus is punished not only for his defiance but also because his actions align with a broader, predestined narrative of human development and suffering. His eternal punishment—a daily renewal of his torment—symbolizes the unending and inescapable nature of fate.

Perspectives on Fate: Divine Will vs. Human Agency

Divine Determinism

In many myths, fate is seen as a manifestation of divine will, an omnipotent force that dictates the course of events. This view posits that everything in the universe happens according to a divine plan, with gods and humans merely playing their assigned roles. The Iliad and the Odyssey, epic poems attributed to Homer, often emphasize this perspective. Characters like Achilles and Odysseus are portrayed as heroes whose destinies are preordained, with their personal choices and actions ultimately reinforcing the divine script.

Human Agency and Resistance

Conversely, Greek mythology also explores themes of human agency and resistance against fate. While fate is a dominant force, several myths highlight the struggles of individuals who attempt to challenge or change their destinies. The story of Sisyphus, who defies the gods and attempts to escape death, exemplifies this resistance. Although his efforts are ultimately futile, his eternal punishment of rolling a boulder up a hill only to watch it roll back down serves as a testament to human resilience and defiance.

The tale of Antigone, who defies King Creon to bury her brother according to divine law, also reflects the tension between human agency and fate. Her tragic end reinforces the idea that while humans can assert their will, they cannot escape the larger framework of fate that governs their lives.

Fate in Mythological Literature

Tragedy and Inevitability

Greek tragedies, written by playwrights such as Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, often center on the theme of fate. These plays delve into the human condition, exploring how individuals confront their destined paths. The inevitability of fate is a common motif, with characters’ flaws and decisions leading them inexorably towards their preordained ends. This dramatic portrayal of fate emphasizes the tragic beauty and profound inevitability that permeates Greek mythology.

Philosophical Interpretations

Philosophers of ancient Greece also grappled with the concept of fate. Heraclitus famously stated that “character is destiny,” suggesting that an individual’s nature inevitably shapes their fate. This philosophical approach intertwines fate with personal attributes, implying that while fate is inescapable, it is also inherently linked to one’s character and choices.

The Stoics, on the other hand, viewed fate as the rational order of the cosmos. They believed that understanding and accepting fate was essential to achieving tranquility. This philosophical stance is reflected in the mythology through the portrayal of wise and accepting characters who find peace in aligning themselves with their destined paths.

By exploring these various facets of fate in Greek mythology, we gain a deeper understanding of how the ancient Greeks perceived the forces that governed their world. From the omnipotent Moirai to the struggles of heroes and the insights of philosophers, fate remains a central and compelling theme that continues to resonate through the ages.

|

|

|